Making Murals the New Monument

by Jordan Taylor

Hot summers in Atlanta during my fall semester of college meant frequent visits to our local corner store. About five minutes walking distance from my alma mater, Spelman College, was the corner store that was always sufficiently stocked with our favorite snacks and drinks, making the hot walk worth it. With each journey down Joseph E. Lowery Boulevard, we not only passed Morehouse College and Clark Atlanta University buildings, but also a distinct mural of Colin Kaepernick on an abandoned building. The mural by Fabian Williams illustrated Kaepernick holding a serious gaze with his helmet in hand. Wearing a Falcons uniform, Atlanta’s home football team, his stature signified the community’s support and respect towards the NFL player’s initial act of resistance in kneeling during the national anthem two years prior, in 2016. Long green lights and heavy traffic often forced me and my friends to wait patiently, giving us the perfect view of the mural. Sometimes we would talk about how detailed the art was or what he could be contemplating, sometimes we would stare in silence and admiration, sometimes we would just glance.

As the fall semester came to a close and the cold weather arrived, our frequent trips became almost rare. It was not until the Spring semester that my friends and I remembered our favorite spot, and decided to take a trip. To our surprise, the building that had previously acted as a display of freedom and camaraderie had been completely demolished and all that remained were pieces of rubble.

Remains of the mural

Seeing what used to make us feel empowered now filled by empty space made me feel as if we lost a piece of our community. The duality of Williams' work was that it acted as representative art to the primary Black local community, reminding individuals of the pride and support they upheld, but also proved as an act of social justice towards those passing by. It confronted the minds of everyday individuals to increase conversations regarding societal inequities. After doing some research, we found that the mural had been taken down in February of 2019 prior to Superbowl LII which was hosted in Atlanta.

Despite his work being destroyed, Williams responded by painting eight additional murals around Atlanta to replace the initial piece. He stated that , “Symbols matter man. You destroyed the whole building it was on? If I were an interpreter of performance art, what message would you take from that?”. Williams' passion and determination to continue pursuing his message could be recognized in his initial mural on Joseph E. Lowry, but his dedication in building more murals is extremely admirable; he is an artistic activist.

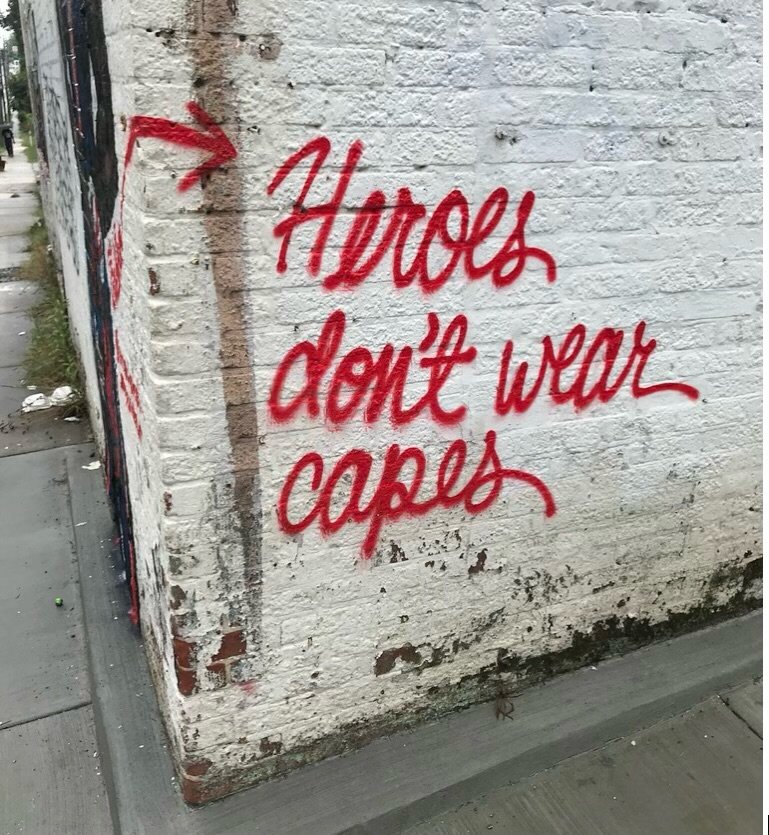

Black activists, or representational figures, historically do not receive the recognition they deserve on a national level. I’m sure we can all relate to school or family trips to see local monuments only to learn about hundreds of white men and few Black models. For primarily Black communities, like the West End in Atlanta (previous home of the Kaepernick mural), murals act as monuments. Despite not being able to see Black representation in larger tourist settings, I could learn about myself and my people through the activism and even radical moments of joy in Black community art. We did not have to go far to see pieces that allowed for free speech in our community, work that inspired us to be strong in our identities. This is why we must re-value the worth and expertise of community art and murals, whether painted, printed, or graffitied. “The idea of defacement as a political act has an important role to play in the current struggle over decolonization,” claims Dr. Tom Houseman, from the Department of Politics and International Relations at Leeds Beckett University. The removal of labeling community art as ‘vandalism’, he stated, “is about confronting the presence of history in the present.” We must use this moment, this rise in street art, as a point of reclamation. Black voices and experiences will be heard whether people want to hear them or not. Waiting on a platform is not always necessary, rather mural artists create their own space to be heard. In creating art, Black street artists re-establish the power within their own communities.

Following the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, propelling the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, a rise in mural and community art tying to social justice began. In fact, almost 30 different states painted murals that read ‘BLACK LIVES MATTER’ on main streets. Artistic community activism is a constant reminder to stay outraged and committed to the cause. Creating a piece that speaks to their opinion on social issues commands the public to contemplate the issue almost as much as the artist themselves did.

“Black Lives Matter" street mural was a collaboration between the City of Charlotte, Charlotte is Creative, Brand The Moth, BLKMRKTCLT, and local artists like Nakima. From conception to finish, it took 72 h

Art is unique in the way that it can be beautiful and emotional at the same time. Although, beauty is not always defined by how appealing something presents, rather it is that which simultaneously holds an intangible intensity and provokes action.

Next time you see a mural in your community, make sure that you observe and appreciate the work.

Sources:

https://www.latimes.com/sports/super-bowl-kaepernick-mural-20190203-htmlstory.html

https://egyptiantheatre.org/importance-of-arts-in-social-movements/

https://www.kqed.org/education/213364/what-role-can-art-play-in-creating-social-change-2

https://www.sbnation.com/2017/8/30/16228620/colin-kaepernick-atlanta-mural

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20201209-the-street-art-that-expressed-the-worlds-pain

https://www.artshelp.com/how-street-art-keeps-the-black-lives-matter-movement-alive/